reprinted from Matter no. IV

On Jumbled Rocks

By Gary Wockner

We have converged on Joshua Tree National Park,

eleven of us, from

A reunion of sorts, our entourage all used to

live in

The sun shines brightly as we leave the town of

Sparse, indeed. The

Joshua trees, at their thickest, stand about a hundred feet apart. Creosote

bush stands intermittently between them with little else but a few other

shrubs and bare ground to fill the arid space. Each piece of life is alive

in its own way, and by its sparseness can be examined as if it stands alone.

The melody of the

When boulders start to appear along the road, our rock climber says, “This landscape is magical.” His pupils dilate as we enter the park, his knee and foot begin tapping the van’s floor, his red hair and face flush, further.

At first we jump around on the boulders using hands and knees without ropes or harnesses. Jumbled rocks are scattered and stacked as if God threw house-sized, rounded, granite dice by the millions and let them pile and lay like forgotten children’s toys. Mounds and mounds, almost to the horizon. A rock climber’s dreamscape. Also a playground where each clump of granite hides two dozen secret passages. And through these passages our daughters create whole lives.

Within an hour the daughters begin to divide themselves. The two youngest, aged seven and eight, run ahead on every trail, climb ahead on every mound, and their voices can be heard from a long distance. They run, and giggle, and look around, and then run some more. They have energy, time is endless, tomorrow never exists.

Two of the older girls, aged nine and eleven, climb more coyly as if there is purpose in it, as if they are seeking something, as if soon they will be teenagers for whom life will hold more than immediate meaning. They think and look and wonder. They watch the other people to see if they are being watched. Their curiosity about the place is mixed with self-consciousness and social need. They will remember.

The girl in the middle, age ten, moves differently. She wears a face, smooth and innocent, the face of every child, but more. On a day when a parent feels relaxed and happy, this child’s face might express simple dreaminess. On a busy, hectic parent’s day, the daughter looks weepy, or perhaps solemn and troubled, and the parent troubles, too. “She is the one that keeps us thinking,” says the mom as we walk along a trail. Indeed, on the landscape, the girl finds her own path different from that of the other children. After a bit of time as the children play on the rocks ahead of us, her father comes over and says, “She seems to realize that the rocks can move, and she knows they could topple.” He says this to explain why she avoids the stacked boulders and the numerous narrow passages that attract the other children. A few minutes later, to explain the same behavior, the mother comes over and says, “She seems to see in geologic time.”

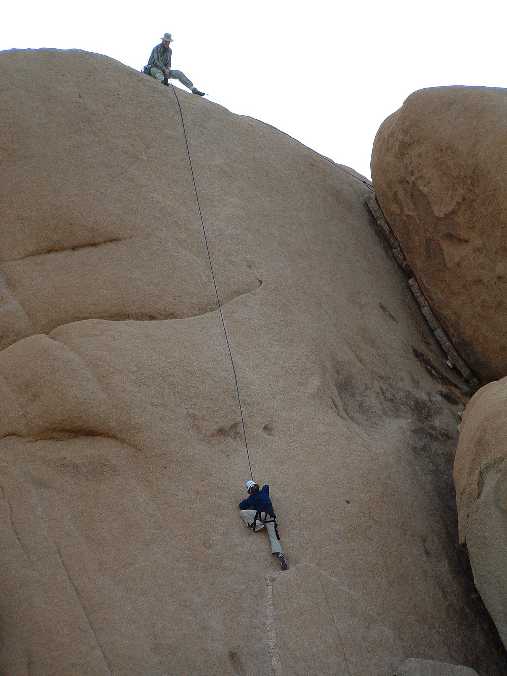

Later, our rock climber secures a top rope on a forty-foot near-vertical but highly variegated wall of granite. He scrambles and jumps like spiderman as if the soles of his feet were suction cups. This is not a first ascent for him, far from it. “5.0,” he says, smiling. He doesn’t need a rope, though the rest of us will. But he understands. Age has crept up on him, too, and his first ascents are in the past. Here, the joy is in watching children climb for the first time. He belays for others, he holds the rope, happily.

The children are exuberant. One-by-one, secured in a harness, they test themselves against the sticky orange rock, and one-by-one they rise as parents watch. Hand and foot-holds are so numerous that every girl can reach the top if she chooses. What stops her is not the climb but her vision of it, as it should be, as it always is. And so by the act of climbing, each young mind also climbs. Where a child goes ten feet on the first effort, she goes twenty on the second, and by the third she reaches the top. The belay, downward, offers her the same.

Personalities emerge that were unknown before. The loudest girl is a careful climber, while another quieter girl climbs ferociously. And with the belay, the expectations are almost reversed. The girl that climbed the fastest tenses as she leans back into the harness and grabs the rope, emptiness beneath her. “Go slower!” she yells down at the belayer as she inches down the wall carefully watching her feet. Other girls walk down the wall like it’s a carpeted stairway, almost prancing.

Our dream girl chooses her own path. On her first effort, she goes up ten feet and looks, weepy-eyed, at the man holding the rope, and then comes down. On her second effort she goes only a few feet farther, but on the way down, she almost dances across the rock, her feet sticking out parallel, rappelling instinctually. Her sneakers scrape against the crumbly rock, side to side, the rope taut. Her eyes dart and widen.

On her third climb, she only goes up half-way, but when she starts to rappel down, her face changes as her legs dance. “I want to hang upside down,” she exclaims to the astounded adults below. At which, knowingly, our climber-belayer says, “Why yes, of course,” and holds the rope tight.

And she does, twirling in mid-air in her harness against the rock, and slowly, ever-so-slowly, her feet meet the sky as her back meets the wall, and then her long arms reach out downward as a smile rakes across her face.

Her own path. Friction and pleasure. On jumbled rocks. From which parents climb, too.