Gary Wockner is an environmental writer and ecologist living in Fort Collins, Colorado. Author of the novel Bicycle Cowboy.com, he did his PhD research on wolf management at Isle Royale National Park and serves as a wildlife advocate on the Colorado Wolf Working Group. Here he writes as a parent who discovers the wild wolf-and the hope it represents-in unexpected places.

Gary Wockner

Soccer Dads for Gray Wolves

We are driving through the south side of Denver on I-25

on the way to our oldest daughter's soccer game. We left Fort Collins

about two hours ago, and right now we are bunched up in a traffic jam

here on Saturday morning amidst a horde of idling, belching beasts-bumper-to-bumper

cars and trucks as far as I can see in front and in the opposing northbound

lane. This year our family graduated from the "Intermediate"

soccer league to the "Arsenal" league, and thus the minivan

gets fueled up and the soccer-road-warrior-mom-and-dad step into high

parental-travel mode.

We are surrounded by cement-the road below, the overpasses above, and

on both sides of the interstate. To our left and right are twelve-foot-high

cement sound barriers and cement walls separating the highway from nearby

neighborhoods. It's got a Blade Runner feel, a postmodern industrial craziness,

a soupy amalgam of automobile-Americana that uniquely displays the paradox

between our always moving minds and down-to-earth geography.

As we inch along near mile marker 205, the scenery suddenly changes. The

strip of sky above our cement tunnel is that brilliant Colorado blue and

the sun is plastering the cement with a healthy golden-gray reflection,

and in that reflection rises an apparition. This urban canyon is covered

with pictures and shapes of nature. The folks who built this slipstream

thoroughfare molded and etched the cement walls into tree leaves, vines,

huge flying swallows, and mountain pictographs. The swallows, in particular,

are car-sized and intricately etched into the cement. These images are

gray and motionless, to be sure, but beautiful in their own cement way,

a kind of twenty-first-century cave art. I am bedazzled.

In an earlier stage of life, I would have interpreted these images differently,

as a kind of simulation, an ironic and distasteful facsimile of the wild.

We are inundated with such ironies, the most obvious of which is that

the land below this interstate was likely once home to the wildness-the

trees, vines, and swallows-pictured on these walls. In a sour mood, I

might have envisioned a Blade Runner future where these wall etchings

were in full color, or maybe contained the video projections of a forest

(with appropriate corporate endorsement every other block) to give us

the feel of traveling elsewhere instead of this urban tunnel. Surely these

cement etchings are the first step in that direction, the wool that we

are ever more interested in pulling over our eyes as we smother the landscape

below.

As if on cue to nudge me into a more hopeful future as we putter along

the interstate, a car pulls in front of ours with a Wisconsin license

plate. I ease up to its bumper as we stop-and-go through this sculpted

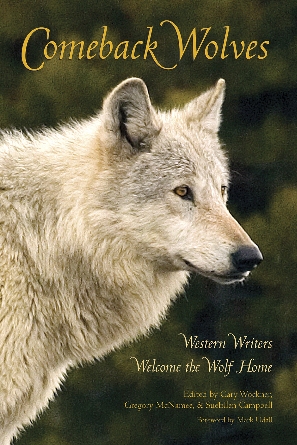

trench. The license plate catches my eye, an image I am familiar with,

showing the picture of a wolf and these words below the image, "Endangered

Resources." And with this image, my optimism rises to the surface.

Several years back, Wisconsin gave its residents the option to pay an

extra twenty-five dollars per year for a special license plate to help

pay for and save endangered resources, the wolf in particular. The program

has been a huge success. It has raised millions of dollars and the wolf

is proliferating across Wisconsin's north woods. When I lived in Wisconsin,

the "wolf license plate" was everywhere, at bumper level, cruising

around the state's highways and backroads. Drivers defined themselves

through this image, and by this image were able to take a material stance,

to make an actual payment for the very thing, not the image, they hoped

to perpetuate-wolves and other endangered species.

I remember seeing similarly used images everywhere in my daily life as

a wildlife advocate-wildlife books that donate to wildlife causes, photo-calendars

that donate to open-lands movements, and the ubiquitous wildlife-cause

T-shirt. And now I see a similar purpose in the cement etchings along

the road. In a very bright mood, I can imagine a host of other images,

an alternative future that is not a simulation but a wool sweater (predator

friendly) that we pull over our eyes and down over our bodies to keep

warm all winter.

Here along I-25, in the most unlikely of places, I am surrounded by images

of nature. I believe I know why. As our family slowly drives through here,

the conversation inside the van livens up. My two daughters, aged eight

and ten, sit in the back and start meticulously viewing and analyzing

the cave art.

"That one's got big wings," says my older daughter about a particularly

huge etching of a swallow. "It's flying right into that mountain."

"Look at those vines," says my younger daughter. "They

look like ivy."

"No," says the older girl, "they're more like pumpkin leaves."

"Too small," the younger girl responds, "and plus, look

at the stem. It's more like ivy."

"Why do you always see swallows at road intersections?" asks

the older daughter. And with that, the conversation complicates and veers

into a nature lesson in which my wife takes an honest stab at answering

that and other questions.

A few minutes later and the conversation turns to the wolf license plate

in front of us. My younger daughter, who was born in Wisconsin, is particularly

interested in why this animal is on that license plate, and as I answer

her question, she becomes even more interested in what Wisconsin does

with the money it collects. The questions and answers get a little more

complicated, and then slowly, the conversation turns to Colorado's efforts

to deal with wolf management and my role in that process. The girls know

I'm on the Colorado Wolf Working Group, and so whenever the subject of

wolves comes up, the topic turns to Colorado's efforts to support and

reintroduce wolves. We spend a few minutes going over the story and I

give them a distilled explanation that brushes on some abstractions like

"endangered species" and "wildness." Fortunately,

they've seen wild wolves in Yellowstone, and so they know real animals

live behind the abstract words.

I certainly don't try to drum anything into these girls' heads, but they

listen intently and overhear, and they know I'm a strong advocate for

wolves. They also know I did graduate work on wolf issues at Isle Royale

National Park, that being the reason for our stay in Wisconsin. But there

are a number of things these kids don't know. Like that before they came

along, dad was more of a hide-in-the-wilderness type than a stand-up-for-endangered-species

guy. And like that their very presence helped galvanize a certain quit-hiding-and-start-standing-up-for-something

mindset. And so finally, as the wolf issue arose in Colorado, dad was

sitting there at his computer pecking away when the idea of "standing

up" took on new meaning.

To be honest, I did not initially jump up and volunteer. Yes, I filled

out the nomination form to be on the Wolf Working Group, but I let it

set there on the edge of my desk for a month until the last day of consideration.

Wolves are extremely political, to say the least, and I knew the stress

level would be very high. My experience at Isle Royale taught me that

wolves are an emotional, visceral topic, creatures for whom the plume

of smoke circling in the air outsizes the fire on the ground by thousands

of times. In the wolf reintroduction projects in the Northern Rockies

and in New Mexico and Arizona, this chaos has only been amplified. People's

opinions of wolves-for and against-flow at hurricane strength. And so

I stared at the nomination form, wondering, "Why would I want to

jump into that?"

But there it was, sitting on my desk, staring back, and for a solid month

I played with the idea. What spurred me to action? No other creature has

ever endured such vehement and totalitarian persecution as the United

States wolf. They have been slaughtered, massacred, butchered, rounded

up, ripped apart, desiccated, desecrated, blown to pieces, and poisoned

by the hundreds of thousands (if not millions) so that finally, completely,

they were uniformly eradicated and exterminated in the continental United

States. What caused our blood to boil so hot? This surely says more about

us, the predator, than the wolf, our prey.

Wolves are now officially endangered through an Act of Congress, and we

have a very strong Colorado interest in recovering them and all endangered

species. And so finally I stared at that form and I said, "If I can,

I should stand up and help get a species removed from the endangered list,

help right this terrible wrong. It would be useful and valuable work."

I was trained, knowledgeable, and available, and if I couldn't stand up

for a persecuted endangered species-a true underdog-then what the hell

could I stand up for?

And as we drive through this chaotic postmodern scene here in the heart

of Denver, our conversation in the car confirms to me that my stand-up-for-wolves

decision was right. We talk a little more about wolves, and then our discussion

turns back to the etchings along the interstate, which gradually change

shape and form to resemble other critters and habitats. A strange conversation,

indeed, to be having in a traffic jam on an interstate highway in a fast-growing

American city. But there it is, nonetheless-we no longer curse the traffic,

we no longer feel the heat and urban oppression. Instead, we wonder, we

talk, we ask questions and we learn things about nature and each other.

We enjoy. Nature, even in simulated form, draws us in and pulls us out.

Instinct seems at work. Wildness beckons. Children's eyes widen, and then

parents' eyes widen in return. I can't imagine what the hell else I ought

to be doing. In my mind, the phrases "species extinction" and

"wolf extermination" have no place on this earth. "Reintroduction"

and "restoration" are the only credible choices.

* * *

The traffic jam finally eases up, and we quickly speed up

to our normal seventy-mile-per-hour jaunt through south Denver. In a few

moments we arrive in Dove Valley near the southern end (for now) of the

ever-sprawling Denver metropolitan area, our destination for day's soccer

tournament. As I look across the soccer complex-a twenty-acre irrigated

bluegrass oasis-I see houses and strip malls marching east across the

plains. But even here a kind of optimism and wildness lives.

As I walk around the soccer fields, a couple hundred young girls are either

playing or warming up and a couple hundred more parents are sitting along

the many sidelines. People yell out, "Go Fireballs," or "Way

to go, Pumas." These are sounds I've heard a hundred times before,

the nicknames we give our teams, evoking, I believe, a kind of wildness.

While I wait for my daughter's game to start, I walk around and listen

a bit more. I hear many nicknames-"Jaguars," "Pythons,"

and "Tornadoes." And strangely, a quarter-mile to the north

sits the Denver "Broncos" headquarters, an orange and white

monolithic building looming over the soccer complex.

Out on the soccer field I see a kind of wildness, too-girls screaming,

running, and kicking. They knock each other around, knock each other down,

and then they get right back up running and kicking again. They yell at

each other as they race on and off the field, and they yell at each other

all during the game. They are, after all, "Jaguars" and "Pythons"

and "Tornadoes," wild and relentless with victory in their minds.

After my daughter's game ends, we slowly walk back to the van, making

our way among the mass of parents, daughters, minivans, and SUVs. As we

pass one field, I am again heartened at the possible future before us-a

team of eight-year-old girls swirls in a huddle readying for their game,

their hands piled high in the middle. In a shrieking cacophony, they recite

a little cheer I've heard a hundred times over the past five years, yet

they have a little twist at the end, a new, uncommon nickname:

We don't wear our mini-skirts

We just wear our soccer shirts.

We don't play with Barbie dolls

We just play with soccer balls.

Go, Go Gray Wolves!

And off they go, little gray wolves, running and screaming

onto the field, our future alpha females of the human pack.

You might ask if this matters, this nicknaming, this image making, and

it is a fair and honest question, for we have nicknamed ourselves many

things over the years of our exterminating and extinguishing. I believe

it does. I believe it helps us express what we wish to see and helps us

speak for those who cannot speak; it is a kind of hope, perhaps, or a

longing for wildness. What is an image, after all, but our attempt to

imagine a different world?

Here in the heart of Denver and the surrounding suburbs, our imaginations

are desperately needed to keep the wildness alive in the rest of Colorado.

To have a healthy, sustainable population of wolves, we need our urban

and suburban imaginations working in full force. We will need special

license plates and cement interstate etchings, and many other images,

groups, and tools-and yes, especially, money-to bring this different world

about. We may even need bumper stickers that say, "Soccer Dads for

Gray Wolves."